Originally published in 2001, “Made in Tokyo” is a study developed by the architects Momoyo Kaijima and Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, founders of the Atelier Bow-wow office, together with Junzo Kuroda. The book is a sort of architectural guide which brings together 70 peculiar buildings from the Japanese capital. Rather than highlighting celebrated monuments or works by renowned architects, it turns its attention to unusual typologies shaped by the dense and often contradictory urban conditions of Tokyo.

In the beginning, they explain the adopted methodology for the analysis. They considered three criteria for choosing the buildings: use, structure, and category. The projects are here represented through a 3D drawing, a site plan, photographs, and a short text.

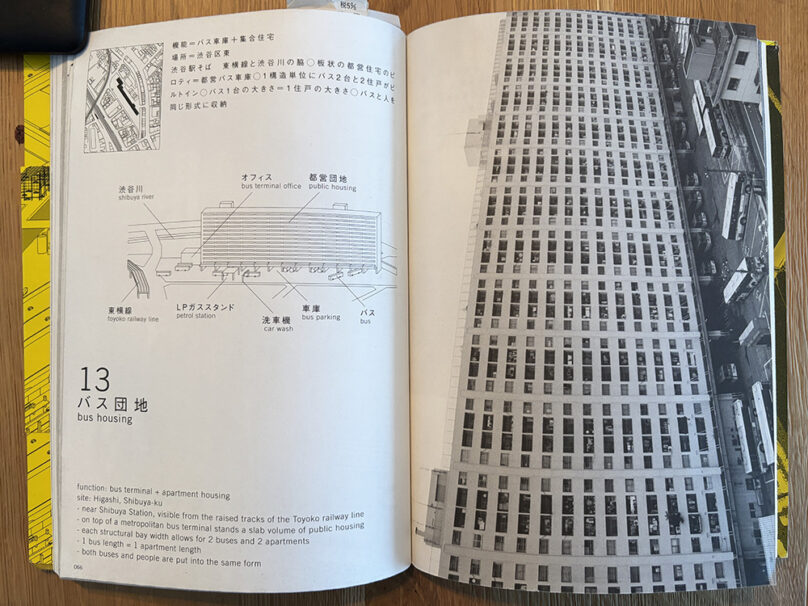

They set out to analyse examples of “Da-me architecture” (which can be translated into “no-good architecture”). These buildings combine unusual functions within a single structural framework. One example is the Bus housing(13), a social housing complex built above a ground‑floor bus garage. The spaces between the pillars accommodate two apartment modules and two bus bays, i.e. the size of each bus is equivalent to that of an apartment.

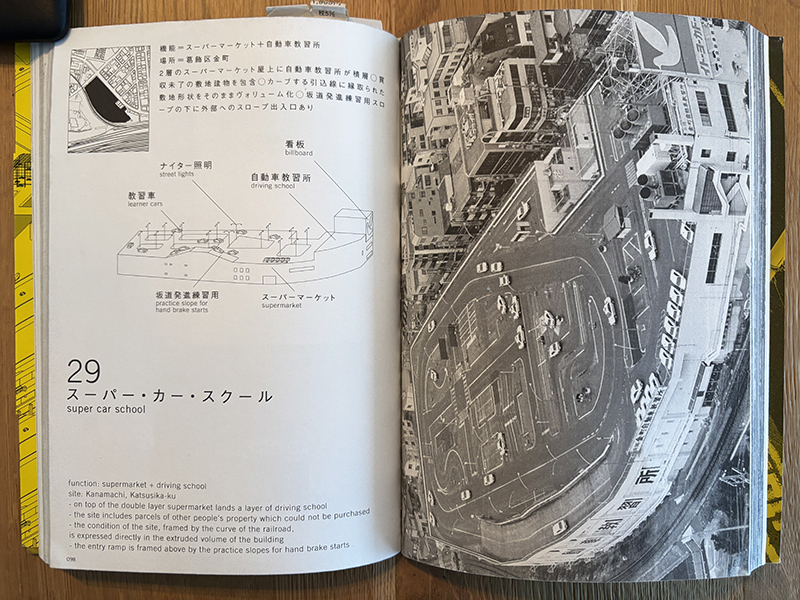

Another example is the Super car school(29), a supermarket with a driving school and a practice track on the rooftop.

Tokyo is a city where the square metre is extremely expensive. As a result, residential units are very small and any spare space must be used. The authors argue that this space scarcity generates a “void phobia” which leads to small-scale architecture solutions, which they call “pet-size architecture”. This phenomenon helps to explain why vending machines are so popular in the country, since they are efficient and fit in almost any corner.

According to the authors, the amount and diversity of “pet-size” architecture in Tokyo’s landscape helps to transform its urban environment into a “super-interior”. This explanation makes a lot of sense to me because, even though Tokyo is a metropolis with over 14 million inhabitants, the streets are still close to the human scale. Many of them are narrow, one-way streets with the sidewalk on the same level, differentiated only by the painting on the asphalt. Depending on the neighbourhood you walk around, you may get the feeling that you are in a small town.

On the other hand, Tokyo’s landscape is also characterised by its many viaducts. In 1964, the Japanese capital hosted the Olympic Games. For the occasion, many elevated highways were built in a short time. The rapid constructions were partly due to the Olympic deadline, but also to the high costs.

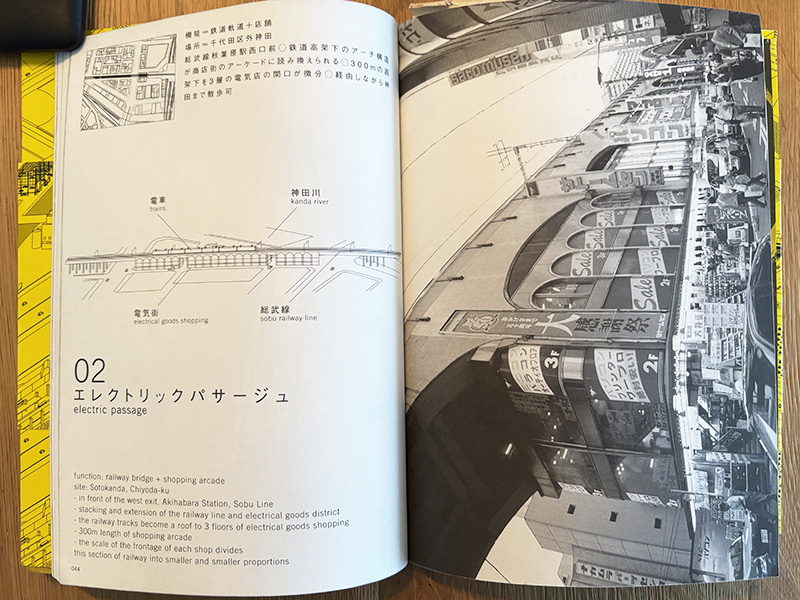

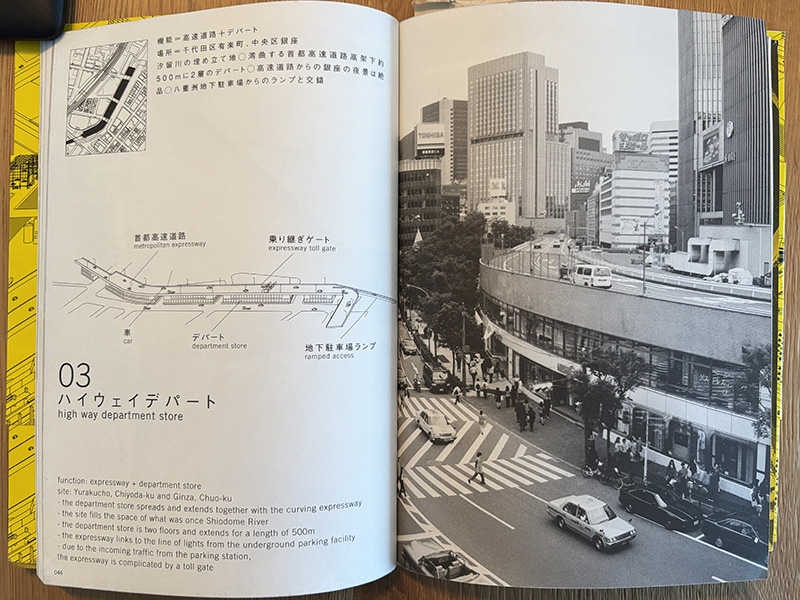

Building in the sky frees up space on the ground. These elevated infrastructures ended up creating several niches, which were later occupied by the “da-me architecture“. Some examples cited in the book are the Electric passage(2), with shops under a train line, and the Highway department store (3), a department store under an expressway.

Many of the buildings analysed are near major transport hubs, be it underground and train stations or an expressway. Initially I felt that this proximity was what influenced the authors to identify them in the first place. However, the adjacency to the transport infrastructure is also a factor that drives the square meter price up, which would explain the overlapping of different functions.

A few examples in the book are directly related to this transport infrastructure, like the Express patrol building (10), which combines police vehicle parking, offices and staff accommodation. This building includes an internal ramp so that cars can directly access the elevated expressway or descend the building’s internal ramp and exit through the road below.

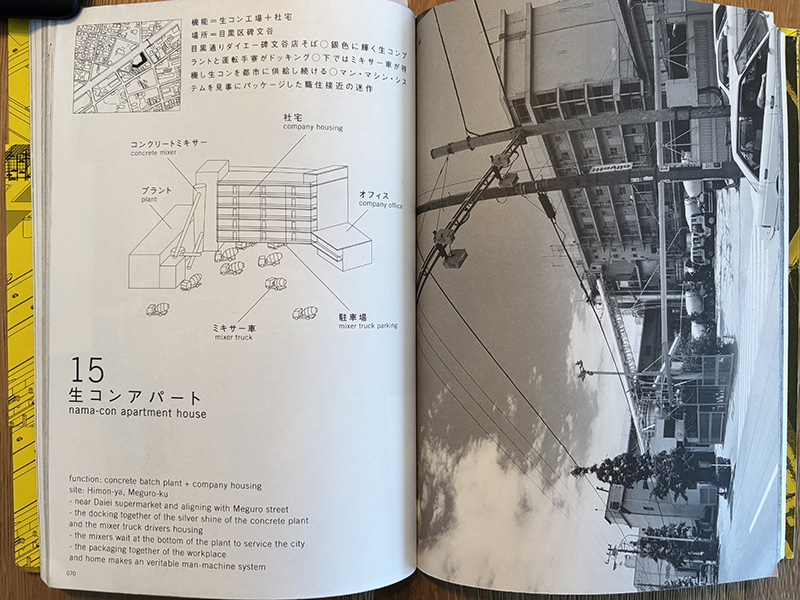

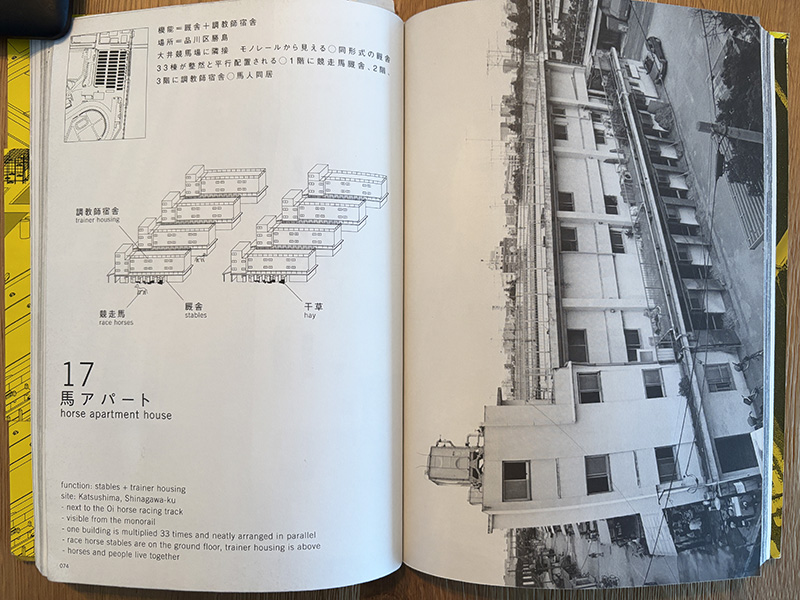

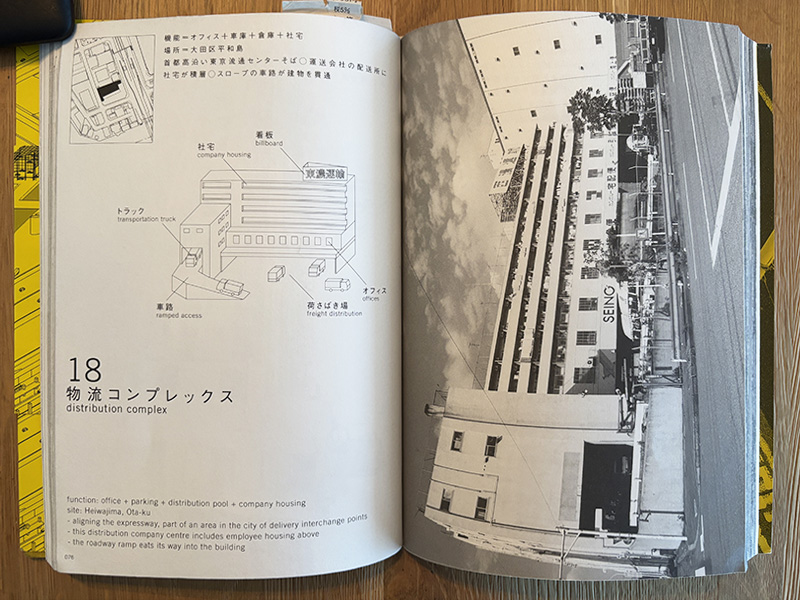

This is not the only example of an office building that also includes housing. Since the price per square metres is so expensive, many people live outside the city and commute to work daily. An alternative to commuting is to live where you work. Made in Tokyo gathers a few examples, like the Nama-com apartment house (15), a concrete plant with housing, the Horse-apartment house (17), a group of buildings where the horse stables are on the ground floor and the carers takers live in the units above, and Distribution complex (18), a distribution centre with housing.

On the book’s final pages, there is a map of Tokyo which shows the location of the 70 analysed buildings. The city is constantly changing, so many of them have been demolished since the book was published. Despite this, the guide is still well worth the read. More than the actual buildings, what I found particularly inspiring from this read was learning about the author’s employed methodology and understanding the dynamics of Tokyo’s urban environment. By looking at examples of architectures which overlap often contradictory functions, we reflect on possible combinations between unlikely uses and how they may contribute to one another.