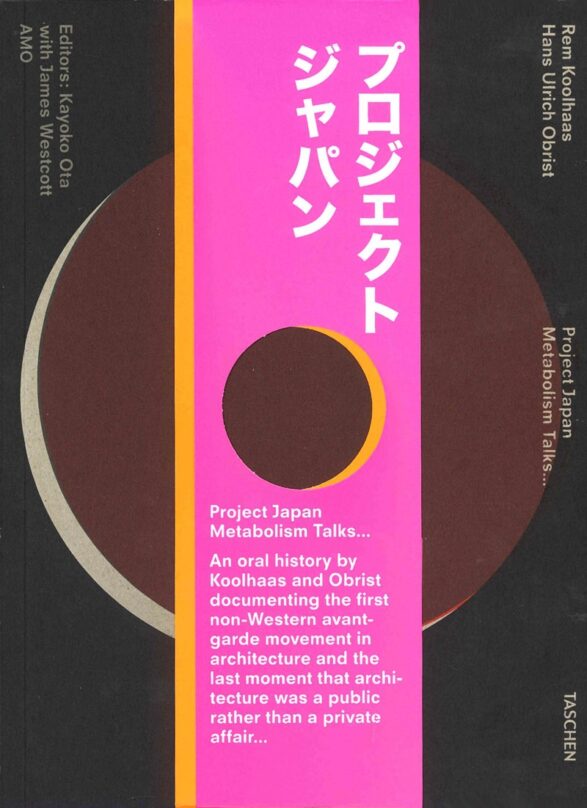

Published in 2011, the book “Project Japan. Metabolism talks…”, written by Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist, provides an overview of Japanese Metabolism, an architecture movement that emerged in Japan after the Second World War. In addition to presenting the historical context, the book includes a series of interviews conducted between 2005 and 2011 with some important members of the movement, like the architects Arata Isozaki, Fumihiko Maki, and the critic Noboru Kawazoe. According to the authors, the Japanese Metabolism was the last avant-garde movement and the last moment when architecture was a public rather than a private matter.

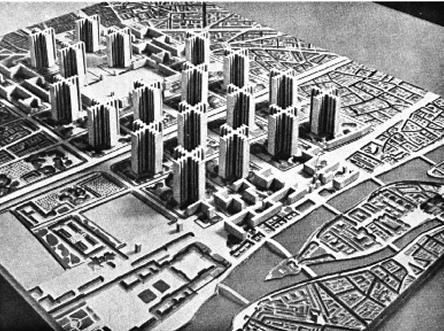

The Japanese Metabolism was greatly influenced by Le Corbusier’s ideas about tabula rasa and the ville radieuse. First presented in 1924 and published in 1933, the ville radieuse was a proposal for building a city entirely from scratch. It seems very radical, but this was the reality at the time for many European cities that had been completely shattered by bombings during the First World War.

In 1932, Japan occupied Manchuria, a region in northeastern China, with an expansionist and colonising project. Unlike the Japanese island, which had a mountainous territory of just 330,000 km², Manchuria was a vast plain covering over 1,3 million km². It was the ideal location for experiments based on the concepts of tabula rasa.

Just 10 years later, with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, Japan was devastated. Tabula rasa was no longer a concept for external expansion, but a solution for internal reconstruction. In addition to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, hundreds of other Japanese cities were also largely destroyed, such as Tokyo, which had 51% of its territory bombed, Osaka (35.1%), Nara (69.3%) and Kobe (55.7%).

In this context, architect Kenzo Tange, who taught at Tokyo University, created Tange Lab, a think-tank that envisioned new solutions for rebuilding the Japanese cities. Their approaches were strongly inspired by modernism, with an eye towards the future yet without losing sight of Japanese tradition.

An international movement

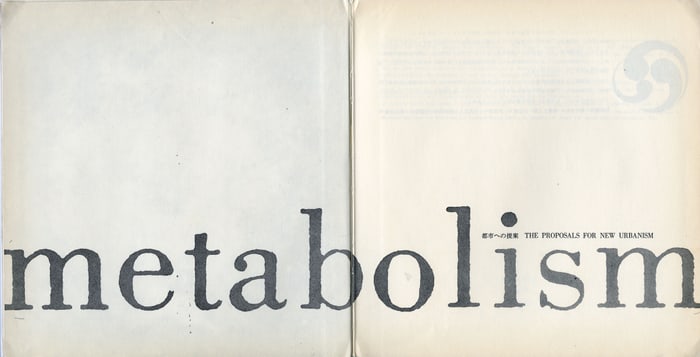

Kenzo Tange spent some time in the United States. He participated in the Aspen design fair and wanted to bring the event to Japan. This resulted in the 1960 World Design Conference (WODECO), an event held in Tokyo that attracted architects from around the world, such as Louis Kahn, François Choay, Bruno Minari, Peter and Alison Smithson, Jean Prouvé, as well as Kenzo Tange himself and the architects from Tange Lab. That same year, the Metabolists’ manifesto book was published.

In addition to Kenzo Tange, architects such as Fumihiko Maki and Kisho Kurokawa spent time in the US and Europe and attended international meetings of the UIA and Team 10, which gave the movement more international visibility.

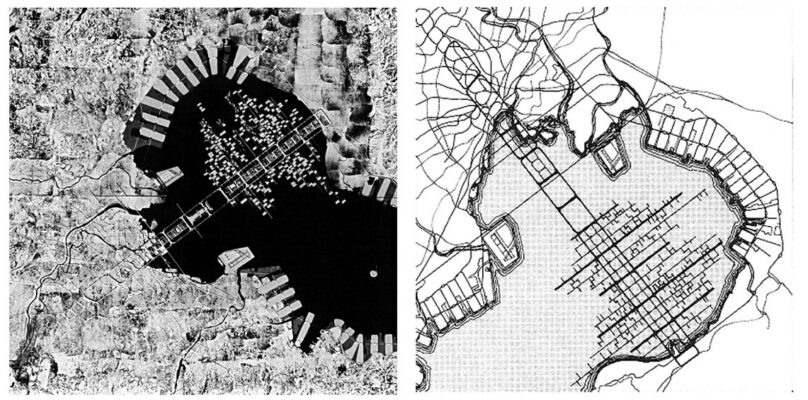

This was a particularly productive period in terms of architecture in Japan. Between 1945 and 1960, Tokyo’s population grew from 3,5 to 9,5 million. Many architects designed urban plans to address the pressing housing crisis, some of which included building over the Tokyo bay (see image below). In addition, megaevents such as the 1964 Olympics (first edition in Japan since the 1940 one was cancelled due to World War II) and the Osaka Expo in 1970 presented opportunities to renew the Japanese identity internationally after World War II.

Heritage and preservation in Japan

The Ise Shrine is often cited as an example of preservation of the Japanese heritage. In a ritual called shikinen sengu, the shrine is dismantled and rebuilt every 20 years. The concept is that tradition is not preserved by the material object itself, but rather by the transmission of knowledge and building techniques from generation to generation. This process strongly influenced the Japanese Metabolism, which is characterised by the transformation and the the movement of parts that make up a system.

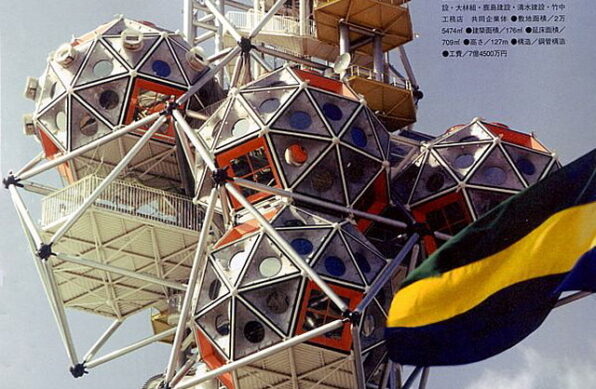

One project that exemplifies this is Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Tower. Opened in 1972, the tower consisted of capsules attached to a central structure. The building could therefore change over time according to the needs. Unfortunately, due to lack of maintenance, the building deteriorated and, in 2007, residents voted for its demolition, which took place in 2022. Until July 2026, MOMA in New York will host an exhibition on the tower entitled ‘The many lives of the nakagin capsule tower”

Another emblematic project is Kiyonori Kikutake’s “Sky House” that the architect designed for himself. The main block was elevated above the ground, supported by a concrete structure. The empty space under the block allowed for the future expansion through the addition of new compartments.

1970 and 2025 Expos in Osaka

The 1970 Expo was yet another opportunity for a tabula rasa, a fertile ground for the Metabolists to experiment. The fair’s initial concept was developed by Uso Nishiyama, and Kenzo Tange directed the master plan, bringing together a team of 13 architects to work with him. Among them were Kiyonori Kikutake and Arata Isozaki.

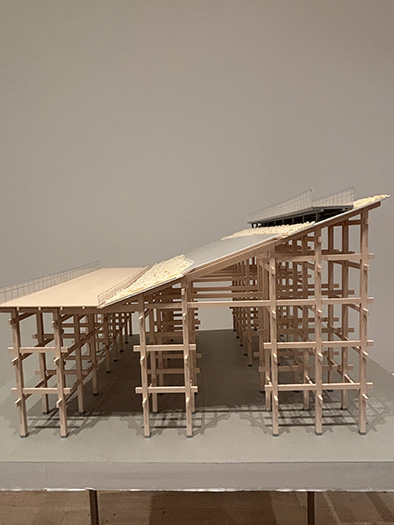

In 2025, Osaka once again hosted the Expo. This edition featured a mega wooden structure designed by SOU Fujimoto, a ring that surrounded the expo area, establishing its boundary and at the same time serving as a circulation space. While the Expo was taking place in Osaka, the Mori Museum in Tokyo organised a major retrospective exhibition of SOU Fujimoto’s work. Below are some photos of the model of the Expo 2025 structure.